UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson has promised that 2021 will be ‘a year of British leadership’ where the UK ‘can look forward with confidence to shaping the world of the future’. There has rarely been a moment in recent times where the UK government is potentially so well placed to demonstrate global leadership. The UK is hosting the G7 summit in Cornwall beginning at the end of next week and COP26 in Glasgow later in the year. Alongside this, a US administration with a renewed global ambition provides an enormous potential opportunity to foster change.

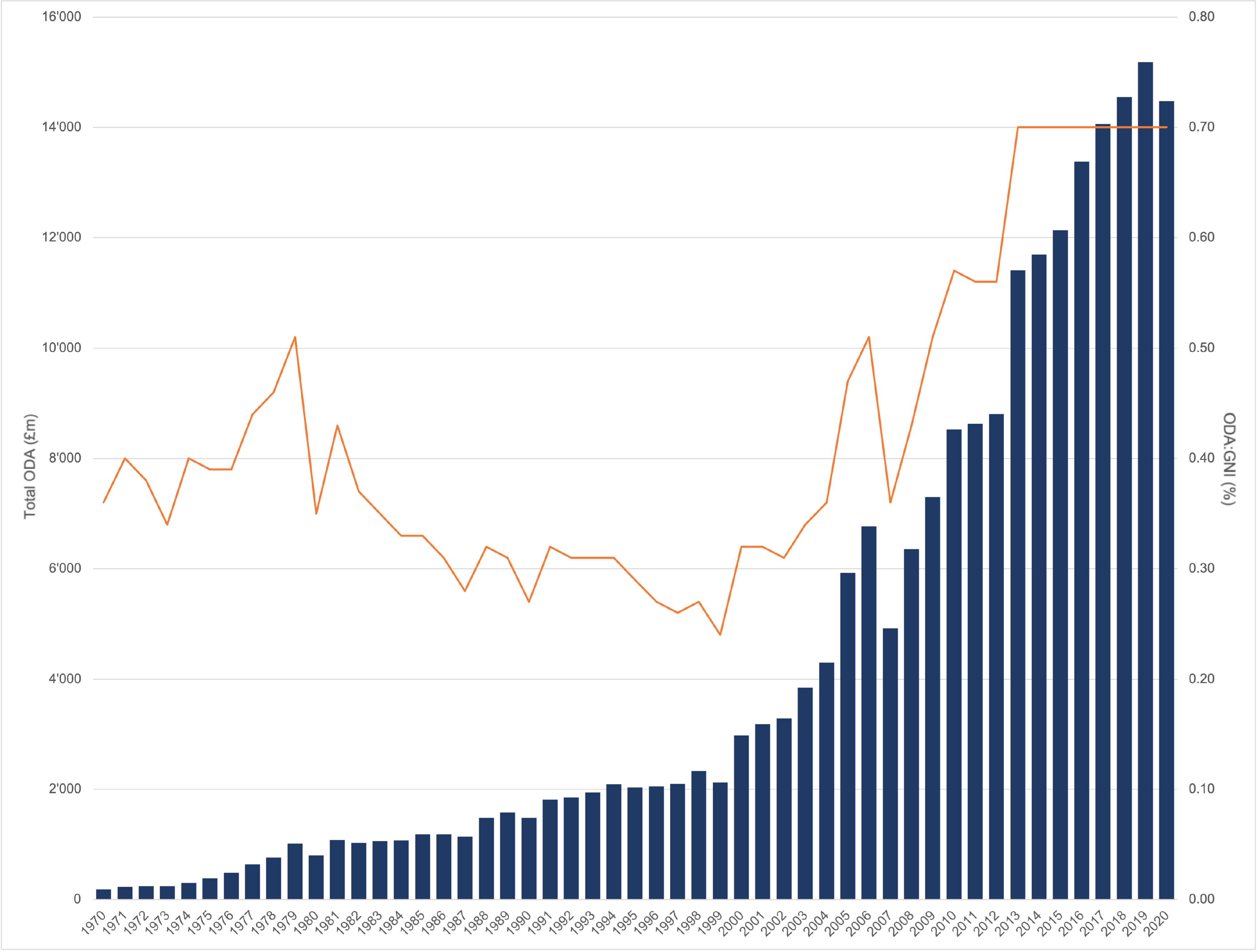

The UK has a track record of effectively using summits and multilateral channels to collectively resolve global challenges. In 2005, when the UK hosted the G8 summit at Gleneagles, governments agreed to write off the multilateral debt owed by a group of highly indebted poor countries. As Figure 1 shows, the UK increased its official development commitments by more than half in 2005 and 2006 to demonstrate leadership and crowd in commitments from other countries. While this increase was only temporary, a total of $40 billion was written off.

Figure 1 UK ODA spend increased significantly in 2005 and 2006 to crowd in debt relief commitments

The UK’s leadership and moral authority have however taken a hit in recent months. While its own vaccination programme has been effective, the fact that the UK has now ordered the equivalent of 10 doses for every adult in the country (second only to Canada) has given rise to accusations of vaccine nationalism. The UK is also yet to lend its support to the proposal by India and South Africa to temporarily waive intellectual property rights on Covid vaccines and medical tools. The UK has also been much slower than other G7 nations to back US proposals for international tax reform. This has raised questions as to whether the UK is more committed to protecting its overseas territories than working towards a fairer global tax system.

Perhaps the most significant contributor to the UK’s ebbing authority relates to recent cuts to the official development assistance budget, the only OECD nation to significantly reduce contributions so far this year. Barely a week goes by at the moment without a new announcement of drastic funding cuts. It is hard to ask others to put cash on the table when you’re seen to be taking yours away.

Resetting the UK’s international reputation

Since the November 2020 spending review (when the government announced its plans to cut back ODA to 0.5% of gross national income), economic prospects in the UK have much improved. The economy did not shrink by as much as feared in 2020, and the Bank of England has revised forecast growth for 2021 upwards, from 5% to 7.25%.

Agreement on a $650 billion issuance of special drawing rights means that the UK will receive a one-off windfall boost to its foreign exchange reserves equivalent to almost £20 billion. This is unlikely to make much difference to the UK’s own recovery plan: indeed, the sums pale in comparison to the £344 billion of support to the domestic economy committed as of March. Even so, £20 billion is a significantly larger amount than the £4 billion cut from the aid budget.

To help reset its international standing, the UK should announce at the G7 summit that it will use this £20 billion to make a multi-year investment in ending the pandemic and supporting a just and green global economic recovery. Such a commitment would place the onus on other G7 nations to follow suit. The mechanics of this are not completely straightforward, but it does not seem beyond the limits of human ingenuity. This analysis from David Andrews suggests the simplest way to put these resources to use would be for the UK to donate its existing reserves rather than the new SDR asset.

UK Chancellor Rishi Sunak should make clear to parliament and the UK public that this one-off investment in a global recovery is not being funded through taxes, but through the extraordinary issuance of SDRs. The money has come from the international system and is being invested back outside of the UK to support recovery in countries that are still being ravaged by the pandemic and have fewer resources to fight it. Using this funding outside of the UK would also help address potential criticisms of additional spending creating inflation risks: it would be deliberately aimed at helping to restore flagging demand outside the UK.

There are three clear areas of the G7’s agenda where the UK should start putting such a financing commitment to work.

A windfall investment in a global green recovery

1. Bringing an end to the acute phase of the Covid crisis

The success of the G7 summit will be judged primarily on whether concrete measures are agreed to accelerate the global response to the pandemic. Indeed, for much of the world – and especially for invitees from India and South Africa – talk of ‘building back better’ in the wake of coronavirus is likely to feel premature. Global rates of recorded infection have never been higher than in April. Access to vaccines remains highly unequal across countries. You do not build back better while the war is still raging.

There has perhaps never been a public policy challenge where national and international interests are so closely aligned as combatting Covid-19. The spread of variant B.1.617 is making it increasingly apparent that the greatest risk to the recovery is virus mutations in populations where the pandemic is not yet contained.

There will also rarely be a global challenge where the UK’s capabilities are so well placed to help forge effective solutions. While the UK’s economic and military power will continue to decline, in the field of global health the country does have claim to something approaching ‘superpower’ status. It has been a long-term and generous supporter of research, as shown in recent trials of a malaria vaccine that could genuinely be world-changing. The UK government can also point to its record in supporting efforts to strengthen health systems.

Accelerating a global immunisation campaign is also clearly in the self-interest of G7 members. The cost to the global economy if the world is not vaccinated could be between $2 trillion and $9 trillion. Accumulated GDP losses to date globally are expected to be $35 trillion. Relative to the size of the SDR issuance, the financial costs of ending the pandemic are relatively small (even if the logistical complexity may be under-estimated). The UK should commit, with the other G7 nations, to funding two-thirds of the $35 billion that the IMF has estimated is needed to end the pandemic. ODI analysis shows that a further pledge of £1 billion from the UK would constitute its ‘fair share’ of meeting this gap in financing.

The UK should also rally G7 nations behind the recommendation of the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response for a donation of close to 1 billion vaccines. This would involve clear commitments and timetables for when G7 countries will begin donating surplus vaccines. In February Johnson said that the UK would donate its surplus vaccines, but unlike other G7 nations no concrete commitments have been made.

The UK could also follow the lead of the EU in committing to further investment in research, development and manufacturing capabilities outside the UK so that supply chains for vaccines are more resilient. Now that the UK vaccination programme is well advanced, UK production of the Astra Zeneca vaccine could be made available for export.

2. Laying the foundation for a more just global economy

The latest IMF projections highlight the divergent prospects for economic recovery. Part of this is a result of unequal access to vaccines, but also stems from the role fiscal policy has played and is expected to play in providing crisis relief and investment in recovery. There is a real risk that, in some countries, the Covid crisis bleeds into a long-term debt crisis and prolonged economic stagnation.

The UK could set aside a portion of its windfall from SDRs to support debt relief initiatives as part of a more ambitious plan on sovereign debt restructuring. This must include relieving debt from multilateral institutions – a UK windfall donation could help finance that.

Efforts to attract the voluntary participation of private creditors in any debt relief have failed. The UK could encourage G7 nations to provide a clear signal that they will work through the G20 later in the year to agree a statutory approach for private creditor participation in debt relief. Without such commitment from the G7 nations, complaints that China is not doing enough on debt relief will continue to ring hollow.

3. Financing a climate response

There is already much to commend in the UK’s climate change response: it has the most ambitious 2030 targets of any large economy. The UK has also achieved impressive emission cuts domestically and been a champion of climate action abroad, including through generous climate finance.

If the UK is going to continue to lead by example, the next decade will require difficult and expensive upfront measures to support further decarbonisation in the UK (e.g. building retrofits and transport electrification). In the wake of a pandemic that has increased inequalities at home, the UK could be a pioneer in just transitions, generating lessons for other middle- and high-income countries that will have to navigate structural economic change, job losses and stranded assets. There is a long legacy to manage here (for instance, closures of coal mines in Wales or railway links for small towns in England), but in advance of the G7, the UK could urge laggards such as Australia, India, South Africa and the US that face comparable challenges to lead on this together, and learn lessons from one another.

Supporting investment outside the UK will remain critical. As Sarah Colenbrander suggests, the forthcoming COP26 negotiations over the new climate finance goal are widely expected to either bridge or exacerbate divides among parties that risk poisoning other elements of the climate negotiations. Further squeezing ODA budgets to ringfence a climate finance target will undermine the UK’s credibility in this area.

The UK could use its windfall from SDRs to capitalise development banks in support of building sustainable infrastructure in middle-income countries. As argued by Chris Humphrey, a capitalisation of the multilateral development banks allied with key operational reforms could help release a wave of infrastructure development. Capitalisation of smaller regional banks or even large national development banks could also promote competition between development banks, pushing some of the more established institutions to be more responsive to their borrowers.

Looking beyond the G7

The G7 summit could be a useful stepping-stone where nations present indicate their commitment to supporting a global recovery. The UK should also signal that further discussions around investment in global recovery will take place at the G20. The government could also indicate that SDRs will be channelled through a series of multilateral and regional investments (rather than bilateral aid programmes), signalling a renewed and welcome commitment to internationalism.

It would be a stretch to suggest that the UK has been a global leader in the first half of 2021, but it is not too late to set out a more positive vision for Global Britain.

The authors would like to thank Tom Hart and Sarah Colenbrander for their comments on previous drafts.