In the Colombian rainforest’s pre-dawn hours, a loud, ugly noise shakes Flor awake. She hears her daughter-in-law call ‘avalanche!’ before rushing into the night with her family under a deadly flow of mud and rocks.

The 2017 Mocoa landslide was Colombia’s worst disaster in decades. More than 300 people were killed and hundreds more went missing.

Flor survived the disaster, but her husband did not. She was one of thousands who came to Mocoa to seek refuge from armed groups. Nobody warned her that the small town was dangerous for other reasons. Surrounded by mountains and six rivers, Mocoa is a hotspot for flash floods and landslides which could easily strike again.

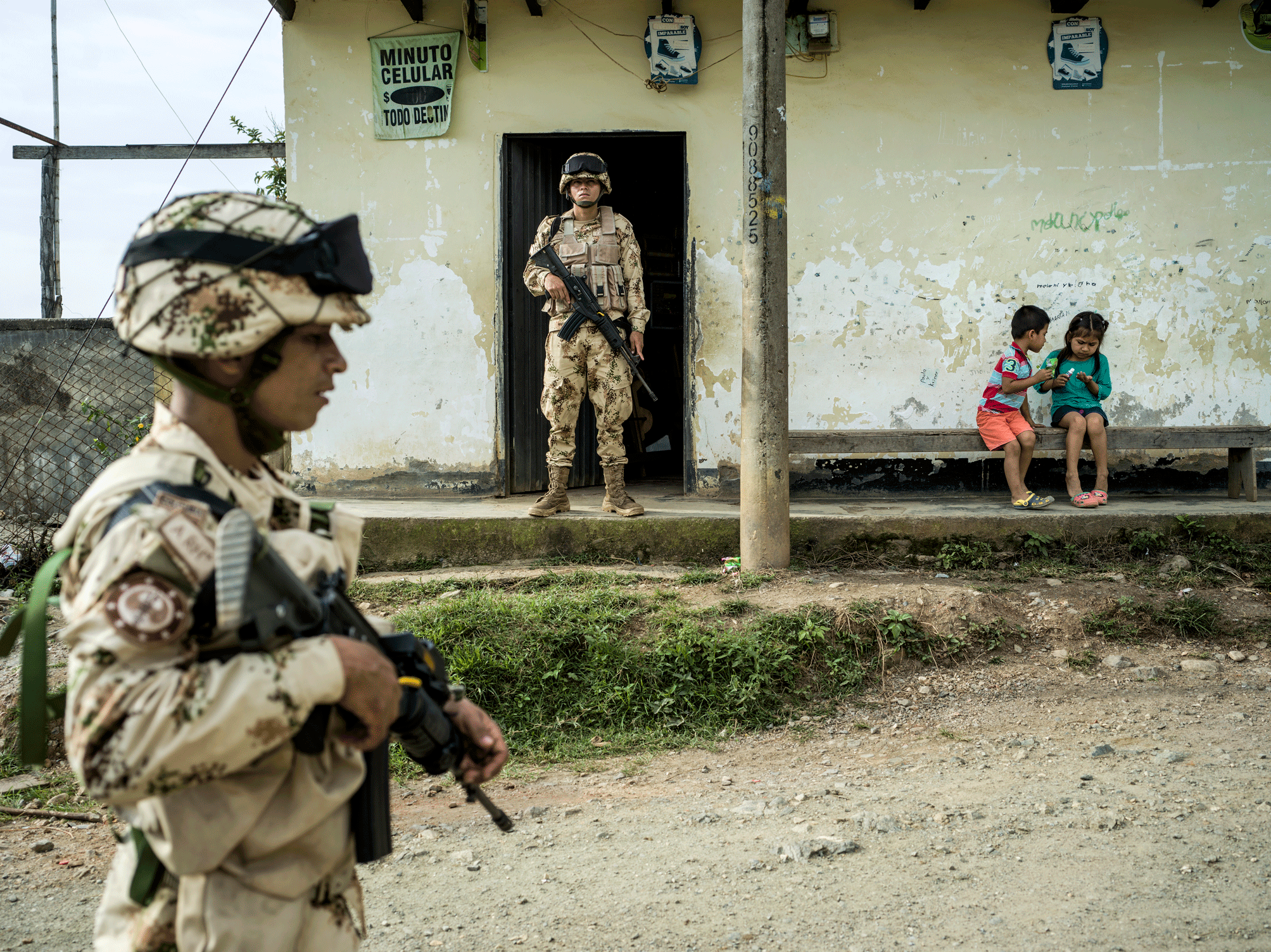

Some survivors were relocated, but many had no option but to stay in damaged homes. They were trapped by high rents in the safer part of town and the threat of attack beyond its borders. Around the world, the double vulnerability of conflict and disaster are part of many people’s daily lives. But this is not by chance.

Almost 80% of the landslide’s victims were also victims of conflict. Violence in Bajo Putumayo had forced them to flee to Mocoa. Without safe affordable housing many people constructed their own homes, and with insufficient disaster planning by authorities, exposure to natural hazards increased. It is little wonder the scale of the devastation was so high.

A 2016 study reveals that 58% of people killed by disasters live in the world’s 30 most fragile states. Even then, the numbers of people affected are vastly under-reported. Although the international community does respond to these events, areas in conflict receive comparatively little aid for disaster risk reduction.

For every $100 spent on emergency response in fragile states, only $1.30 is spent on disaster risk reduction and preparing for future disaster events.

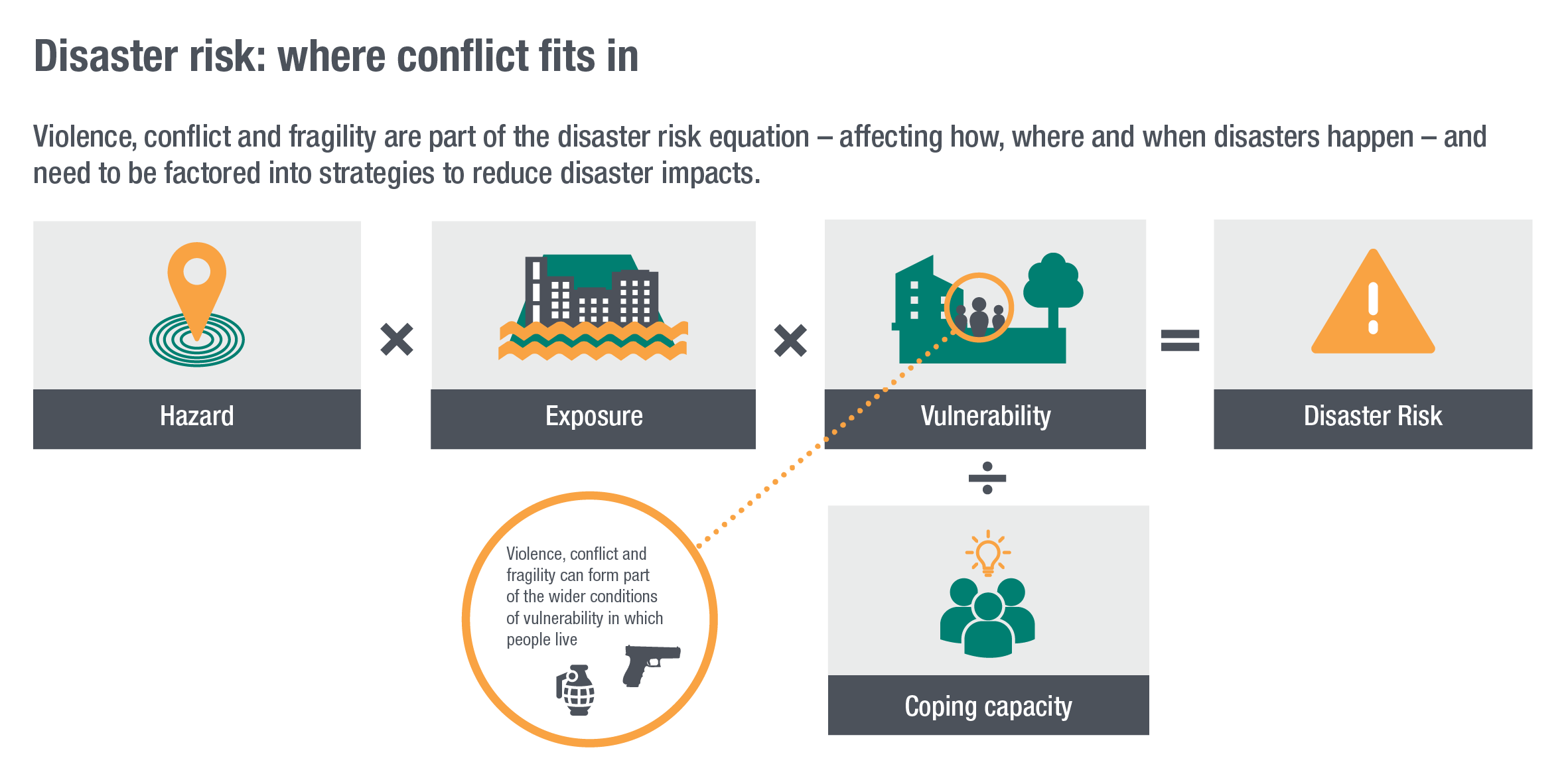

Despite this clear need, policymakers, practitioners and funders promoting disaster risk reduction have for too long neglected to pay special attention to contexts of conflict. Little is known about how conflict increases people’s vulnerability to disasters and impedes the attainment of disaster risk reduction goals.

As a result, states and their citizens in contexts of conflict, fragility and violence often lag in preventing and reducing disaster risk, increasing the likelihood of setbacks to hard-won economic progress and sustainable development.

The Overseas Development Institute (ODI) interrogated disaster risk reduction financing, policy and programming to understand the role of conflict, fragility and violence in disaster risk. Our review of over 50 years of research shows how conflicts are deeply embedded in societies and can exacerbate vulnerability to natural hazards.

We are currently developing an understanding of what types of disaster risk reduction actions are appropriate and viable in different conflict contexts to ensure we really can ‘leave no one behind’.

There are many forms of conflict, from sexual and gender-based violence to sectarian conflict and high-intensity armed conflict. Each, in different ways, undermines how states, their citizens and the international community pursue disaster risk reduction.

Conflict disrupts disaster risk governance and the implementation of disaster risk reduction strategies, curtails funding and ultimately reduces people’s capacities to cope with, prevent and reduce the impacts of natural hazards.

In countries where peace and stability are not the norm, conflict exposes fault lines in society which are rarely accounted for in standard approaches to disaster risk reduction. Consequently, a context of armed or violent conflict is often considered too difficult an operating environment for the delivery of disaster risk reduction strategies and programmes, even if the risk of natural hazards is high.

In situations of armed conflict or in areas controlled by non-state armed groups, disaster risk reduction is likely to be a low priority for governments and international agencies. Action is often limited to protection and response. Over a prolonged period, authorities often lack the technical capacity, political will and resources to act in the interests of the long-term disaster resilience. Or in some contexts, the accepted authority to do so.

Loretta Hieber Girardet, Head of UNISDR Asia-Pacific, explains why communities that have been affected by conflict are doubly vulnerable to disasters.

We know that populations living in conflict-affected areas, especially countries and communities that have been experiencing conflict for long periods of time, they have reached a high level of vulnerability already. They’ve seen their livelihoods reduced, they may be displaced, they may be living in camps, basic services may be limited. So, their vulnerability levels are high, their capacities are often quite low, and when you add an additional hazard, a hazardous event, their risk level is much higher than those living in stable environments.

Achieving the ambitions laid out in national and sub-national disaster risk reduction strategies in conflict contexts is often complicated by the destruction of infrastructure, and the absence of key institutions. Programmes can be interrupted and stall when tensions escalate. Accessibility to those at risk can be constrained by safety concerns. The more protracted the conflict, the more these conditions undermine the attainment of disaster risk reduction policy and practice.

Where disaster risk reduction is pursued, policy directives and investments are often piecemeal and response-driven. In Colombia, armed groups continue to compete for territorial and political control in the wake of the state’s limited presence, despite the peace agreement in 2016. At the sub-national level, limited capacity and resources limit the much-needed transition from preparedness for response to long-term risk reduction practices.

Compounded by high levels of insecurity and restricted access, investment in reducing people’s vulnerability is often foregone. Even where disaster management plans exist, they are significantly underfunded. Colombia has the highest exposure to disaster risk in South America, partly because so many people are forced to live in conditions that make them vulnerable to natural hazards.

Read our report on ‘Doble afectacion’: living with disasters and conflict in Colombia

In Lebanon, conflict presents markedly different challenges. The fractured political system often requires compromise for the state to function. This also applies to disaster risk reduction efforts.

The district capital Tyre is not only at risk of earthquakes and flooding, it is also vulnerable to violent conflict due to its proximity to the Israeli border. During rebuilding efforts following the 2006 Israel-Lebanon war, new disaster preparedness and response mechanisms were set up.

Because of sectarianism in Tyre, authorities struggled for over two years to unite its four ambulance services under one management team, as each had different socio-cultural affiliations. Eventually a compromise was reached. Rather than having a single lead service, all four were given equal status, and operate under the same preparedness and response mechanism.

Lebanon reminds us that there is no blueprint for disaster risk reduction. In conflict-affected contexts, compromise and managing competing interests are part and parcel of identifying entry points for disaster risk reduction.

'The people are hungry to receive training on first-aid, on firefighting, and want equipment to help them feel safe.' – Kassem Chaalan, Disaster Risk Reduction Programme Manager, Lebanese Red Cross.

There has long been an assumption that disaster risk reduction happens in relatively peaceful and stable contexts. Though conflict makes attainment of disaster risk reduction outcomes more challenging, it’s time to change the way we think – and act. The risks and impacts of both conflicts and disasters are not a given; it’s within our power to reduce both.

Contrary to popular perceptions, it is neither too difficult to undertake disaster risk reduction in conflict-affected contexts, nor a low priority for many at-risk communities. In fact, it’s already happening. The question now is whether states and the international community are willing to acknowledge this and do more to act.

What’s more, conflict-affected contexts could offer opportunities to advance disaster risk reduction and help find innovative ways to manage the impacts of natural hazards. We know that disaster risk reduction is only effective in conditions of conflict if it has been adapted accordingly.

In Afghanistan, aid agencies need to negotiate with armed state and non-state actors, including warlords and commanders, to gain access to certain areas. In the absence of disaster risk reduction tools specifically designed for conflict situations, staff must rely on experience, negotiation skills, and a lot of patience.

'We need to use specific methods for project implementation in terms of conflict prevention and social disorders, while considering do-no-harm.' – Abdul Halim Halim, Managing Director, CoAR

Disaster risk reduction interventions themselves can be sources of social conflict. Acknowledging this, the Afghanistan Resilience Consortium developed conflict analysis tools to assess conflict risk and adapt interventions accordingly. Their approach centres on a commitment to ‘do no harm’.

Although these tools are not explicitly oriented towards conflict resolution or peacebuilding, they produce information on contexts and people’s perceptions that can help reduce the risk of social conflict.

Elsewhere, the Coordination of Afghan Relief (CoAR) operates a community-based disaster risk reduction programme which builds infrastructure, including protection walls, and provides education and skills-based training on disaster risk. CoAR also follows do-no-harm principles, uses tools to identify project risks and develops strategies to deal with them.

Read our report on Disaster risk reduction and protracted violent conflict: the case of Afghanistan

While adapting approaches is one option, conditions of conflict can provide an entry point for disaster risk reduction. In Lebanon, public concerns over internal and cross-border armed conflict far outweigh those over natural hazards.

But this presents an opportunity for those working in disaster risk reduction. Many civil society organisations view training in emergency response, first aid and search and rescue as a way to build skills to respond to both conflict and disasters throughout the country.

The Lebanese Red Cross (LRC) are pioneering emergency preparedness in schools across the country. In Tripoli, schools provide an entry point to promote disaster mitigation to communities through joint activities with conflicting groups to ensure safety and reduce tension.

The LRC terms this a ‘conflict-sensitive’ approach to disaster risk reduction. It focuses on social cohesion and integration, alongside training in emergency response and first aid for youth.

In Saida there are often violent clashes between the occupants (and their different factions) of Lebanon’s largest Palestinian refugee camp, Ein El Hilweh, and the Lebanese Army that monitors its borders. When these occur, the Community Emergency Response Team park their ambulances outside the refugee camp and coordinate with community leaders to treat the wounded. In short, this city-level understanding of ‘disaster risk reduction’ includes first aid for weapon-wounded.

The Ein El Hilweh camp also shares a perimeter wall with an elementary school. As part of its holistic approach to risk management, the LRC reinforced the wall to protect the students and created an emergency escape route through the basement which leads to a safe street.

Buy-in from the Ministry of Education has been critical to advancing disaster risk reduction capacities. It is now building on the established relationship between the LRC and school authorities to also encompass earthquake and fire preparedness.

However, this alternative approach is only effective under certain conditions. School buildings must be made resilient to multiple threats and hazards, and local communities must be willing to adopt risk management practices. Nevertheless, the work underway demonstrates Lebanon’s commitment to mainstreaming conflict sensitivity and enhancing its capacity to respond to both types of risk.

For years, opinions have been split. Many governments, donors, operational agencies and United Nations (UN) entities concerned with disaster risk reduction have resisted engaging in issues of conflict. Their hesitance became apparent during negotiations for the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015 – 2030, which identifies global targets for reducing disaster risk.

Despite a global commitment to support those most affected by disasters, backstage politicking at the negotiations revealed deep concerns around conflict. Many were happy to leave it completely off the negotiating table.

A desire to keep discussions focused on natural hazards and away from the politics of vulnerability saw all references to ‘conflict’ removed from the final draft. Failure to include explicit recognition of additional challenges that conflict presents to states and non-governmental agencies in achieving disaster risk reduction outcomes has reduced incentives for donors to invest.

It has also limited the evidence base and generation of tailored approaches for conflict contexts. For many, Sendai was a missed opportunity to take conflict-affected contexts seriously and has kept the issue in the dark.

Margareta Wahlstrom, Head of the Swedish Red Cross and Former Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General for Disaster Risk Reduction.

When we discussed the Sendai [Framework], many of the countries that actually pushed very hard for the inclusion of conflict did so, I would say, based on their experience of crisis, conflict and disasters. But they were the classic donor countries, the western countries. I think that was part of what created this sense of unease. Many of the countries that actually live in conflict and increasing disasters are countries that also traditionally need and receive much humanitarian assistance for conflict situations.

On regional and national levels, conflict is treated in quite different ways within disaster risk reduction strategies. In Lebanon, the national Disaster Risk Management Unit approaches conflict and natural hazards within the same policy framework. In Africa, the impact of conflict is acknowledged at the regional level in disaster risk reduction declarations, while some national strategies make no reference to conflict at all.

Nevertheless, most states and non-government organisations continue to struggle, using ill-adapted approaches to disaster risk reduction. Strategies and tools are built on assumptions such as the state being able and willing to protect vulnerable people.

Yet in countries mired by insecurity, the building blocks needed for basic disaster risk governance are often limited. In some cases, the ruling party may even increase disaster risk for marginalised communities. In these situations, a state-centric approach may not be the best way to achieve fair and equitable disaster risk governance, as this requires a certain level of institutional functioning and political will.

Where the state is unable to lead on disaster risk reduction, community-based action is a viable alternative proven to reduce vulnerability to disasters. But 'the community' should not be romanticised. Conflict can permeate inter- and intra-community interaction and can be a site of exclusion and marginalisation. Externally funded projects tend to be time-bound or geographically limited. Local action needs to be better supported in sustainable ways astute to conflict dynamics.

We do not know enough about how to work with states and authorities in conflict contexts to bolster states' capacity and their obligation to protect everyone on an equal basis. Nor do we know under what circumstances disaster risk reduction can help rebuild trust between the state and its citizens in a way that ‘leaves no one behind’.

In Chad, the legacy of civil war has impacted the social contract, financial resources, institutional strength and the technical capacity to implement conventional approaches to disaster risk reduction.

A high turnover of officials has also limited the effectiveness of a working group on disaster risk reduction. Well intentioned policies and plans in place are hazard-specific and fragmented, devised largely in response to specific crises.

Read our report on Pursuing disaster risk reduction on fractured foundations: the case of Chad

For countries like Chad, a simple conclusion could be that we need to 'do more’: invest more financial resources and provide more technical support. But where disaster risk reduction is a relatively new concept for many states and where capacity is limited, we may need to rethink our approach.

In Chad, climate change, drought and food security hold more political weight than disaster risk reduction. Part of the reason is because they often come tied to external funding. If working under these sectors achieves disaster resilience, we may need to put our disaster risk reduction flags down and find more creative ways of achieving the same goal.

Disasters are political. For people living in conditions that make them vulnerable to natural hazards, including the displaced, this means disaster risk reduction is a rights issue. Displacement can increase vulnerability to natural hazards, and disasters can result in displacement until a solution is sought.

In Colombia, people displaced by conflict are struggling to claim their rights. Many internally displaced and indigenous people in Mocoa affected by the landslide were not invited to participate in drills. Even in the aftermath, their involvement in rehabilitation planning was extremely limited.

Local people asked: who was responsible for keeping them safe in the first place? What caused the disaster?

Explanations vary depending on who you ask. For some, it was an unavoidable disaster caused by climate change and heavy rainfall. For others, it was the local authority’s hastiness and lack of care during town planning. And for certain officials, it was the decision of the individuals concerned to move to a hazard-prone area.

Francely was displaced by armed conflict in Colombia and relocated to Mocoa, where she was a victim of the deadly landslide.

When I arrived, I lived in rented accommodation, but then they sold me a cheap house in front of the hospital. The problem now is that since the house is located in a risky area, they no longer let me work on the house. My case is similar to many other people’s here. Nothing can be done here, but they do not give us a solution.

Here in Putumayo, the victims have no rights. A long time ago, a colleague who was a teacher in Nariño received a house in Nariño after living there for two years. Instead, I have been here for 17 years, we have not received anything.

Disasters and conflict resulted in 28 million new displacements in 2018. The total estimated 68.5 million people currently displaced within their country and across borders often face increased exposure to natural hazards such as floods, landslides and severe storms. For host countries, this draws attention to the question of whether and how to protect not only citizens, but displaced people, regardless of their legal status. This is especially important in countries like Lebanon, where refugees make up around 30% of the population.

Yet refugees are not included in Lebanon’s disaster risk reduction architecture at the national, sub-national or local levels. There is also little consensus around how to include refugees and internally displaced populations in disaster risk reduction coordination and planning.

While this is not unique to Lebanon, refugees and internally displaced populations are falling through the cracks in conflict contexts without disaster risk reduction approaches that cater to their needs.

Lebanon’s reluctance to create permanent spaces for refugees and their subsequent ‘no-camp’ policy has forced 350,000 Syrian refugees to live in informal settlements. Here, refugees face severe winter storms in ill-equipped temporary shelters. In January 2019, Storm Norma forced at least 600 Syrian refugees in Bekaa to relocate due to heavy floods and damage to shelters.

For these refugees, safety and freedom from violence are not guaranteed rights. Fundamentally, disaster risk reduction in conflict contexts is an issue of protection and rights. The lack of adequate provisions only increases their vulnerability to conflict and disasters.

Disaster risk reduction in conflict-affected contexts is not well documented. We do know that achieving progress in disaster resilience in these contexts is the most challenging – and most pressing. We need to better understand what actions are appropriate and viable.

This doesn’t mean doing more of the same. It means really understanding the conditions of conflict to advance and inform disaster risk reduction policy and practice.

For years, disaster risk reduction has been based on assumptions that don’t hold true in many contexts of violence, conflict and fragility. In peaceful and stable societies, the natural hazard, or the state's responsibility to protect its citizens, is often the starting point.

But conflicts around the world require the disaster risk reduction community to be more politically astute. To achieve the Sendai Framework’s targets, we need to acknowledge that violent situations are fundamentally different. Therefore, disaster policy and programming must be different too.

Rather than prescribing the conditions needed to pursue conventional approaches to disaster risk reduction – equitable governance systems, sufficient financial resources and robust legal frameworks – we need to acknowledge the limitations that may exist: lack of trust between the state and its citizens, limited tax base and low technical capacity.

Only then can disaster risk reduction mature in a way that genuinely supports states, agencies and local organisations in conflict contexts. The international community can follow suit; to develop better ways of supporting willing but unable states to pursue disaster risk reduction.

There will never be a single solution, but creative ideas and options are already out there. A human rights-based approach could help close the gap for programmes not explicitly designed to address marginalisation or exclusion.

'Conflict and fragility is the reality for many countries, so we cannot exclude that when we look at disaster risk reduction policies.' – Mami Mizutori, Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General for Disaster Risk Reduction.

A rights-based approach to disaster risk reduction could also help confront people’s vulnerability to conflict and disasters, and hold duty bearers to account. Other options include adapting implementation approaches of disaster risk reduction strategies and programmes by mainstreaming principles of 'do no harm', embedding conflict sensitivity, or even linking with conflict resolution and peacebuilding approaches.

To be truly effective, disaster risk reduction needs to start with the political context – not the natural hazard – and the vulnerabilities of those affected by both conflict and disasters. Only then can we prevent the escalation of conflict into armed conflict, and natural hazards into disasters.

In the future, disaster risk reduction may even empower and support affected people to move toward conflict resolution.

In many places, peace and stability are understandably a priority. But this does not negate the urgent need for disaster risk reduction for those who need it most. To truly leave no one behind, the disaster risk reduction community must recognise this reality, and not shirk its commitments in conflict-affected contexts.

By engaging in and understanding contexts of conflict for the long-term, we can develop new approaches that reduce disaster risk and safeguard some of the world’s most marginalised and at-risk communities. Now is the time to step up to this challenge.