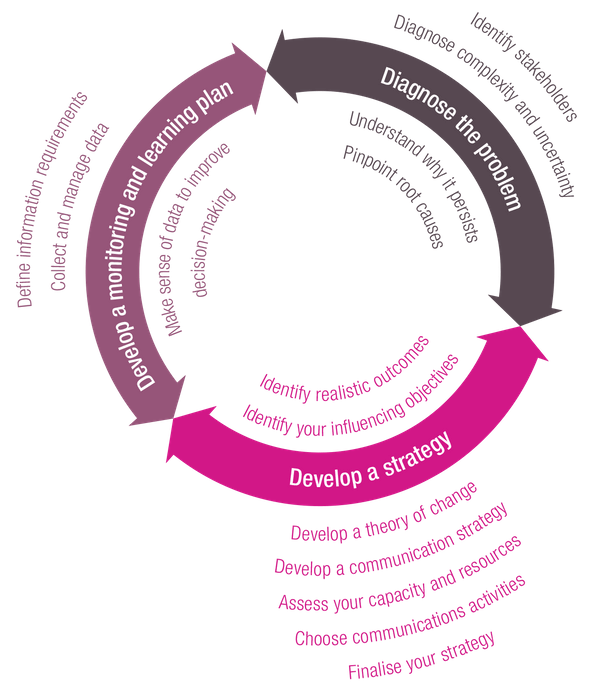

ROMA consists of three main activities, each of which is broken down into a series of steps. These are described in detail throughout this guide.

Figure 1: The ROMA cycle

Each step is associated with a set of tools, to be used with partners and stakeholders to develop a shared understanding of what the objectives are and what needs to be done. In some cases, these tools will be a series of questions to be answered with research and analysis; in others, they will be workshop or interview techniques. Policy processes can be highly political, sometimes involving dense networks of actors and coalitions with competing values and interests.

Engaging with policy in these types of environments requires a collaborative approach, and ROMA has been designed specifically to facilitate collaborative engagement. Drawing on the principles of Outcome Mapping (OM), each of the stages includes tools to help groups and networks of policy actors coordinate their work and learn together.

Diagnose a problem

This chapter shows how important it is to diagnose your problem thoroughly, so you address the root cause of the problem rather than its symptoms. Carrying out a thorough diagnosis will help you understand better what issues you need to work on, with whom and what their motivations might be for working with you.

ROMA offers different tools for this: you can do a first approximation with the ‘five whys’ technique and a more detailed diagnosis with the fishbone diagram. The case study from Nepal demonstrates that changing policy is by no means the only goal: there are many other issues that need to be addressed to improve the way, for example, migrant workers are treated.

The second part of this chapter helps you further diagnose complex issues. ROMA offers you a clear analytical framework for building your problem diagnosis in some detail into your objective and approach. Larger programmes could carry this out as an in-depth analysis, but smaller projects and programmes may not have the resources to do this.

However, discussions around the different headings (such as whether capacity to implement change is centralised or distributed) will help you focus on key challenges and raise issues that can be further addressed as you work through the rest of the ROMA process.

Develop a strategy

This chapter is the heart of ROMA: a set of workshop-based tools to engage your stakeholders around a clear objective and develop your plan. The tools can be used separately or together, and in any order: each builds on the other to add layers of analysis. The centre of ROMA is the idea, taken from OM, that sustainable change often results from incremental changes in people’s behaviours, not just in the outputs they produce.

Once you have described your initial objective, setting out the changes you would expect, like and love to see is a useful way to think about the outcomes and impacts your work can deliver. The process provides a useful first check on how realistic your initial objective is and explains the theory of how change is likely to come about.

Good communication is central to ROMA and throughout the life of any policy-influencing project. Communication serves different purposes: influence will not come about by simply disseminating the results of your work and hoping they will be picked up. The more complex the problem you are addressing, the more likely it is you will need to adopt a knowledge-brokering approach.

This will involve strengthening communications within networks of people and organisations, facilitating a collaborative approach to problem-solving and being involved in debates about change and how it happens. ROMA helps you understand what sort of communication and knowledge-brokering roles you could choose and what sorts of effects they are likely to have.

Monitor and learn

This chapter helps you ensure you learn, efficiently and effectively, about the strategies you have put in place to achieve your objective and how to improve them. Traditional monitoring approaches, which rely on predefined indicators, do not work well in complex situations where the context changes (sometimes rapidly), new stakeholders come in and out of the picture or new evidence emerges. ROMA helps you develop a monitoring strategy that is appropriate to your purpose, the scale of your project and the context within which you are working.

This does not mean it is a light-touch approach: far from it. ROMA helps you prioritise your needs for monitoring; how you balance the need to be accountable to funders with the need to build trust among your stakeholders or how to balance the need to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of your operations with the need to deepen your understanding of the particular context you are working in.

There are no fixed answers. Instead, ROMA helps you make a reasoned judgement, and decide on the different tools you could use to collect the information you need and make sense of it.

As suggested by Figure 1, ROMA is full of feedback loops. It is a process that encourages constant reflection on how you have characterised the policy problem, your plan for approaching it and how you manage the implementation of that plan. Within each chapter we provide internal links, encouraging you to move between the chapters.

Outcome Mapping (OM) was developed by Sarah Earl, Fred Carden and Terry Smutylo from the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) as a way of planning international development work and measuring its results. OM is concerned with results – or ‘outcomes’ – that fall strictly within the programmes sphere of influence, and it works on the principle that development is essentially about people and how they relate to each other and their environment.

The focus is on changes in behaviour, relationships, actions and activities in the people, groups and organisations it works with directly. At a practical level, OM is a set of tools or guidance that steers project or programme teams through an iterative process to identify their desired change and to work collaboratively to bring it about.

For more information, visit the OM Learning Community.

It is worth noting that ROMA draws heavily on the concepts underpinning OM. Developed in the early 2000s, OM is an approach to fostering change that centres on understanding how different actors behave and how changing the behaviour of one actor fosters change in another. The context within which policy change happens is a complex one, happening with a range of different actors at different levels, as our Diagnose the problem chapter outlines.

Over the years, the RAPID team has found that OM-based approaches help organisations navigate this complexity to understand how policy change really happens and what they can realistically hope to achieve. In the team’s experience, OM-based approaches perform better in this regard than approaches based largely around delivering specific outputs to specific deadlines.

Policy

We define this fairly broadly as a set of decisions that give rise to specific proposals for action. Many people equate policy with legislation, but it also includes non-legislative decisions such as setting standards, allocating resources between organisations, changing the levels of subsidies or taxes or consulting specific groups in the policy-making process.

Influence

In general, we define influence as the goal to be achieved – the evidence of your influence on a decision or set of decisions.

Normal

In general, we define this as the means of achieving that goal.

We refer to both influence and engagement, depending on the context. It is difficult to completely separate influence and engagement: greater influence may lead to improved engagement, or better engagement may lead to greater influence. It will be up to individual readers to define how they see the relationship between influence and engagement in their particular context.

As noted, ROMA is an approach to improving how you engage with policy to influence change – it is not a blueprint for making policy change happen. As our next chapter shows, most development problems are complex and cannot be addressed by interventions based on an idea of linear change. Where the problem itself is complex, the environment within which policy is made will also be complex, and there are too many unknowns to just roll out a plan and measure predefined indicators.

Learning as you go will need to be the hallmark of your strategy: using the phrase ‘it’s complex’ should become a trigger for interesting exploration and reflection – not a means of ignoring difficult issues that do not fit your plan.

Second, ROMA is a whole system approach – not a step-by-step methodology. The steps and tools outlined in Develop a strategy fit together in different ways, and there is no single ‘best’ way to use them. It is important to understand all the ROMA steps and how they relate to each other before working out where to begin planning for policy influence. ROMA is also scalable: it can be applied to a small intervention, such as the promotion of research findings during an international event, or to a large multi-year programme or campaign to bring about changes in a particular sector.

Third, ROMA is a process of constant reflection and learning – it is not just a means of collecting better data or an evaluation methodology. Because it can be complex, policy engagement faces many different challenges: what the goals really are, who to engage with, how to do it and how to cope with evolving contexts. Overlaid on that are challenges any organisation faces, such as demonstrating financial accountability and good governance, and achieving objectives efficiently and effectively.

This means collecting information about a variety of issues over different timescales while ensuring data collection does not become an end in itself. Monitor and learn outlines the different reasons for monitoring techniques that link learning to action.

No individual part of the ROMA toolkit will give you a single right answer to the question of how best to engage with policy. While they are probably best used in the sequence shown, at each step you will be encouraged to reflect on whether you need to revisit previous actions in the light of work completed. For example, developing your engagement strategy may reveal gaps in your change theory; revising this may lead you to add nuance to the outcomes you can expect and thus prompt you to broaden your policy objective.